Beyond the Screen Door, Chapter 1

Cancelled for thoughtcrimes, I’m sharing this, the first chapter of Beyond the Screen Door, till I can find a publisher willing to republish my novel in its entirety. To be continued…

Nora Lee Sutter

August 1945

The Unborn

IT WAS AN unusually hot summer that year. I was seven. My mother had been pestering me to speak for days. Terror held me silent. Something unknown was weaving itself to my skin. Five nights had gone by since death stood at my bedside, and although he was playful, pleasant, and four years younger than me, he came with a paralyzing message.

“Do you think it’s a boy?” my mother asked.

I shrugged.

Our hands were pasted together in the thick August air. My mother wobbled along beside me. Dirt swirled on the curvy road. It was a long walk and my mother’s feet were swollen. She was eight months pregnant and covered in a thin layer of sweat. She wore her favorite housedress of pale yellow cotton with wild roses so faded, they hid demurely in their own pattern of green leaves.

“You want a nice cool lemonade when we get to Betsy’s house, sugar?”

I nodded.

“Oh, come on, honey bear, talk to me. It gets so lonely having all these one-sided conversations.”

I wanted to say something, I really did, but the words were stuck. When you stop talking for so long, you notice how noisy the world is. On the flip side, too much quiet can trick you into thinking you’ve gone deaf.

In the distance a foggy mist formed under the tall trunks of red cedars. It snuck up slowly and rolled toward us in thin waves.

“If you put your hand right here, you can feel him kicking,” my mother said. “I just know it’s a boy. You know how you can tell a boy from a girl, Nora?”

I opened my mouth, but nothing came out.

“See how he lies down low in my belly?” she asked, circling her stomach. “Girls are up higher.” She patted the top of her bump. “You were right around here, honey bear. Sometimes, at night, when everything was so quiet and peaceful, I could feel your heart beating but an inch from my own, and I just knew you had to be a girl. Same as I’m sure this one’s a boy. I don’t think it’s bad luck to find out before he’s born. Do you? I mean it’s so close anyway. And besides, I need to know that I’m right so we can start setting up the nursery. We’ll ask Betsy, and then we can be certain.”

Betsy Ruth Moore was my mother’s best friend, her only friend. She wasn’t the sort of medium you might find at the annual Hoquiam Washington State Fair, sitting behind a black curtain, head wrapped in a scarf, crouching over a crystal ball. Betsy was the real deal. She could see things. Once, she’d been called upon to investigate the Aberdeen hauntings. Another time, she drove miles out to Coupeville, where a schoolgirl’s phantom, often seen walking along a particular road, made news in the local paper. There were spirits around her all the time. Some were a nuisance. Some were pushy. Some were angry, and some, Betsy would say, had more personality than the living.

As we approached Betsy’s house, her wind chimes rang gently. I loved that sound. Betsy told me her husband, Richard Moore—his spirit anyway—would speak to her through the chimes on her front porch. It was their way of staying in touch. He knew how cluttered her field of vision could get, so he avoided standing in the crowd of transparent shadows. He often jingled in agreement at the things his wife said. He was as agreeable in life as he was in death.

Betsy Ruth Moore’s home was magical. I couldn’t wait to go into the house and wished my mother would pick up her pace. Betsy had an apothecary table, a Pandora’s box, that held a collection of meticulously stashed oils. When she anointed candles with them, the peppery scents would creep through the cracks of the doorways and fill the rooms. The aroma of her home was syrupy and spicy all at the same time. It smelled of Frankincense and Azurite. She used Black Star to clear her psychic channels, which were like small buttons she could press to see the invisible ones. Luckily she knew how to click it off if a presence was being creepy.

A month before, under my friend Joanne Waterman’s porch, I’d tried pressing my belly button while lighting a cone of Black Star incense. Joanne watched me—skeptical, curious, flirtatious as always—to see if anything would actually happen. Before the middle of the cone had a chance to glow orange, I gave up and dropped my shirt, a little embarrassed. Why wouldn’t the little boy come? Why would he only visit me when I was alone? It seemed so effortless for Betsy. I wondered if my irises would turn gray, like hers, once I learned the secrets of the spirit world.

My mother was out of breath. Betsy came out and waved. I skipped nearer and flopped down on her porch steps. My mother teetered close behind. She was striking even in her clingy frock—with a cumbersome uterus squeezing all her organs into one tiny bunk. Betsy poured three cups of iced lemonade and gave one to me. Beads of water quickly formed on the outside of my glass. The sweet juice stung playfully at my tongue.

“So, you wanna know if it’s a boy or a girl,” Betsy said.

“How do you always know what I’m going to ask before I ask it?” my mother replied.

“It’s a boy.”

“I already knew.” My mother seemed satisfied with herself. “Guess I just wanted to be one-hundred-percent sure before painting the nursery.”

I wandered away, without having to be told, and crouched down in the tall grass, beaming at the thought of a sibling. I could see my mother and Betsy, their words far off like the buzz of a contented beehive. I collapsed onto blades of grass, which tickled at my neck, and closed my lids at the sun. When I opened them, I saw, clear as a looking glass, the young boy sprawled out beside me. Our eyes were the same hazel brown, shaped like almonds. His skin was pale, and he smelled of sweet powder.

My attention was diverted by a loud argument, and as quick as that, he was gone. Betsy and my mother hollered over one another. I crept toward them, but they didn’t see me there, behind the large bark of a hairy tree.

Betsy frowned. “You need to leave your house and come stay here with me. I’m serious, Peggy Jane Sutter. Do I need to tie you to the damn chair?” The wind chimes rang out compliantly. “See? Even my dead husband has something to say about it.”

My mother placed her hands on either side of the overgrown moon in her stomach and rocked back and forth. “He’d only come here and hunt me down. He’s mean but he ain’t stupid. It’ll only make things worse.”

Betsy scanned the front yard and saw me. My mother’s eyes followed. I picked at the tree and pretended I hadn’t been listening. “Nora Lee,” my mother called. I went quickly and planted myself at her side.

“What about—” my mother began to say.

“She’ll start talking again soon,” Betsy said, staring out at the pines. “She’s scared. Aren’t you, honey?” But when she finally leaned in toward me, she seemed rattled by something. She grabbed me by the wrist and took me in the house, leaving my distracted mother behind. She placed a blank sheet of paper on a wooden table and gave me a pencil.

“What did you see?” she asked.

I shivered.

“Who came to you?”

I wrote slowly, squeezing the pencil tight:

William.

“How old is he?” she asked.

I held up three fingers.

“God help us. If he’s coming to you in the form of a three year-old he must have something to say, something urgent. Is there a warning? Did he tell you anything?”

I tugged at my dress. Did Betsy know him too? I wanted to ask her who he was.

“What did he say?”

I pressed the lead hard on the page:

We have to stop mommy.

Betsy looked as though she were shoved back by a great force. Her lids were so wide her eyes might’ve dropped out.

Half to me, but mostly to herself, Betsy said, quietly, “Just as old spirits can choose to show up younger, the young ones can choose to show up older. Whatever they think will make the most sense to us when they appear. Oh, how clever they are, the invisible ones. He’s young enough so as not to frighten you, and just old enough to form a full sentence.”

Outside, my mother’s chair creaked. I heard her struggle to push herself up. “What’s doing in there?” she asked from the other side of the screen.

“Go on ahead, Nora Lee. Run along and wait by the mailbox,” Betsy said.

Off in the distance, I checked for letters in the box. I flipped the red flag up and down as they quarreled even louder than before. Chimes on all corners of the house rang out in a distressed chorus. There wasn’t a single breeze, and the warning hit me like a swift punch to the liver. My mother came flying out of the house, brown curls whipping behind her, arms raised high in the air, face beet-red. Betsy Ruth trailed after her, pleading. My mother wouldn’t turn back. She snatched my arm and walked swiftly away.

Betsy called out furiously, “You’re neck-deep in denial!”

When we got home, my mother went upstairs and ran a bath. Our fast-paced escape left her winded. The steam came up in clouds until the room was dusty with a thin mist. I climbed onto the tremendous chair that sat under the window. On the foggy glass, I drew several hearts with my fingertip. Then I toweled it off right away, just in case my father were to see and get angry at me for making a mess.

“Come sit with me, Nora Lee,” my mother said. I pulled the heavy chair to the tub. My mother put shampoo under the running water, and soon she was covered in bubbles. Her wet hair hung over the glossy ceramic. Her face was shiny and distraught.

“What should we name him? Something starting with the letter N.”

I shrugged.

“Nathaniel?”

I shook my head no.

“Norman? Nolan?”

No again.

“How about some fancy French name? François?” my mother asked.

I laughed and was startled by the sound.

“I’ve got it,” she said. “We’ll call him William, after my father.”

I jumped out of the chair. It tipped and slammed back in place. My left ear rang loudly, followed by a strange abrupt moment of utter silence. My mother’s lips moved but nothing came out. And then I heard her. “William. Hello, William,” she said to her belly. “See, he won’t answer me either.”

Outside, it began to drizzle lightly, which made the white sky look brighter. I trembled by the window and tried to piece it all together, but it was a great big jumble. We heard my father’s car skid into the driveway. When he slammed the car door, my mother’s body jerked, creating ripples in the tub. She got up, fumbling, covering herself with the robe I held out to her.

“Go downstairs and hide in the hall closet,” she said.

I stood firm. A frail, undersized distraction at best, I knew I’d pose no threat to my father.

“Now, Nora Lee. Move it.”

Maybe it would be okay. I followed orders and ran downstairs to my usual hiding spot and prayed my father wouldn’t find either of us. Gripped with fear, I attempted to rationalize with myself. After all it wasn’t like I could make predictions with any certainty. But when I heard his steps on the gravel, I began to cry, wishing I’d taken my mother to hide. My father fumbled at the door till he managed to find the right key, and then he was inside.

“Where are you?” he called menacingly. “Crazy whore,” he mumbled.

He started up the stairs and stumbled. It didn’t make sense. He’d made a promise. We’d all been to church together that week. He’d gone to confession. And yet, here he was, a demon’s elixir surging through his blood, foul-mouthed and in full bloom.

I got to my knees and pressed my head against the door. His voice became a whisper as he shuffled at the top of the stairs. I knew that shuffle well. Surely he would drop where he stood, black out, and wake much later with temporary amnesia. Relieved, I wiped my face on my mother’s coat, which hung above me.

The house was so silent. Then his footsteps sprang back to life, landing him on the floor just overhead. The radio he kept on his nightstand clicked on and off, on-off, on-off. Our house, thin and hollow, echoed with every vibration that went through it. His angry baritone voice came barreling down through the floorboards. “Goddamn tramp. Goddamn it.” I caved in, pressed my feet against the door, and braced for a showdown.

His heavy boots paced, then made several jumps in one spot, like skipping rope, or a large inconsolable child throwing a tantrum, followed by a quick thunk and a distressed lion howl. My mother cried, an agonizing cry. Something broke against the wall and fell in pieces.

“Fat ass. Get up. This house is a mess. On your ass all day doing God knows what.”

Then a chase. Him clamoring and stomping, and her slippers crawling across the floor. Finally that awful sound of fist hitting flesh. The muffled patter of some helpless creature trying to scurry away.

“John, please.”

Classified 4-F. Unfit for military duty. Those words had changed things. The rejection disgraced him and pushed him further into his sickness with the drink. The rest of the world was spinning quickly around us, but we were frozen. His failure enfolded us in a thick tarnish of stigma. And he, in turn, showered us with scorn.

“Get up, fat ass.”

“John. I’ll take Nora Lee and leave.” The words came out with some hesitation and just a hint of bravado. She’d never threatened to leave. Where would we go?

“You can go, but you sure as hell ain’t takin’ my daughter with you. Or the one that’s on the way for that matter. They’re mine. You’ll be arrested for kidnapping.”

My mother screamed as she was dragged across the wood floor. I knew the sound well. These were the disturbing melodies I’d learned in syncopation with my young vocabulary. There was a struggle and another hit.

“The baby, John. Please. Stop.”

Then I heard something I would never forget: my mother falling down sixteen wooden steps and a cry so painful that I shot out of the closet. Her legs were covered in blood, her robe wide open, her hair across her face distorted with agony. My father stood at the top of the steps, so consumed with rage he didn’t even see me. He paced, cursing to himself.

My path to the next-door neighbor’s house was blurred by tears and the speed of my slight frame. I banged on the door and didn’t stop till Mr. Lynne opened it. When the voice I’d been storing up inside for days finally came spilling out, it was stronger than I expected.

“Mom needs a doctor!”

He paused and looked down at me like he wasn’t so sure I was really there.

“She’s hurt real bad!”

Mr. Lynne shook his head at me, seeming disappointed by the sorry sight standing before him like an apparition. I realized my feet were bare and muddy from the run over in the newly dampened earth. I followed his hard stare to the mess I’d tracked onto his steps.

“Wait here,” he said, going into the kitchen. I saw him lift the phone.

“Please hurry,” I added desperately, envisioning my mother alone in the house with him.

Mrs. Lynne appeared beside her husband. The two figures stood close together.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“What do you think?” Mr. Lynne said. “That creep is over there beating on his wife again.”

I bolted from their front steps back to my house. Afraid as I was, I couldn’t leave her there, defenseless, twisted in a pile.

She was still in the same spot when I returned. Her eyes were closed, and she wasn’t moving.

There were two, purple, crescent-shaped marks on her belly. I curled up beside her in the ghastly warmth of her blood and wrapped my arms around her.

“Mom?”

My father came down the stairs and stood above us. I hid my face in her hair. I smelled the sweet lavender scent of our shampoo and felt a sharp kick to my tailbone. Lights swirled around. Little moths flapped tiny powder wings, caught in a tunnel. Fleeting twinkles exploded in the vast expanding passage, and there was bitty William far off in the distance. Then blackness. Absolute nothing.

From another consciousness, I woke to Mr. Lynne gently tapping my cheeks. My mother lie beside me, staring at the ceiling. I struggled to recollect how we’d come to be placed as we were and surrounded like a freak show. My father was sitting in the room, watching us through dark, squinted eyes. My mother’s hair was still damp. I remembered she’d been bathing. My cheeks burned. Dry blood caked my jaw, arm, and hand. I gripped my mother’s chest. It rose and fell. She was breathing.

The doctor hovered. He tugged at his yellowish beard and flashed a pea-sized light into my mother’s eyes, which he pried open with a thumb and forefinger. He tried to shift her body, which made her scream. He poked her in various places. I’ll never forget the cruel words Dr. Harrisman spoke next. I would puzzle over them many hours to follow, as though they were a riddle that needed solving.

“Let’s rush her over and pull it out.”

At the time I didn’t know what he was referring to. What would they be pulling out of my mom? Which organ would they be removing and how? Her heart, a lung? These were some of the parts that had thus far been rather vaguely explained to me.

“What about the girl?” asked a shaggy-haired young man dressed all in white.

Dr. Harrisman tugged at my legs. “The girl looks fine.”

Weasel-faced Officer McCarthy tried to get an explanation from my father, who wasn’t responding.

“I asked you a simple question, John Sutter. How is it that your wife and small child came to be lying on the floor in a puddle of blood?”

“You’re all idiots,” my father said under his breath. He glared at my mother and showed no inkling of remorse.

Officer McCarthy cuffed my father’s arms behind his back and said he’d push to have him prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. I wondered what prosecuted meant. It sounded like electrocuted. I wondered if my father would have to stick his finger in a socket. My father didn’t put up much fight as he was hauled out of his home.

An ambulance pulled into the driveway. Red lights danced around the ceiling.

“Who’s staying here with the girl?” Officer McCarthy asked.

“They don’t have any extended family. No friends that I know about,” Mrs. Lynne answered.

“You mind staying here? I could send someone over from social services to collect her if it’s an inconvenience.”

“That won’t be necessary,” Mrs. Lynne answered. “Me and my husband will be here. Nora will need a familiar face. Poor girl’s been through enough.”

My mother was carefully placed on a long board. She cried when the two men, uniformed in white, shifted her.

“Where are you taking my mom?”

No one answered.

“Let’s move it,” Dr. Harrisman said. “We don’t want to lose her.”

I followed them to the door and watched through my fingers. I could hardly believe this was happening. My father was in a cop car. My mother was outside in a chalky van that was driving off without me.

Mr. Lynne carried me to my bed. He tried to remove my dress, but I crossed my arms and began to breathe heavily.

“Everything all right in there?” Mrs. Lynne called.

“Everything’s just fine,” he said. He sat on the edge of my mattress. “You’re a good little girl. A sweet girl such as yourself should never be exposed to the likes of your father.” As he tucked my bed sheet under my chin, his face changed and his sham of a hard shell melted away. The rest I don’t remember, only the sound of his voice and the steady hum of a lullaby, lyrics of what category I cannot recall.

THE NEXT DAY when I awoke, it seemed as though it had all been a nightmare. My father would be sitting at the local pub, playing hooky as other men lined up for work. My mother would be in the kitchen, scrambling eggs with a splash of milk. But then I felt the sharp pain in my tailbone. My clothes were still stained with blood, a crude confirmation of the night before. I called out, but it wasn’t my mother, rather Mrs. Lynne, who came to my bedroom door.

“Oh, dear. We’ve got to get you cleaned up, don’t we? Come now, we’ll run you a nice warm bath.”

We went upstairs to the bathroom where my mom had bathed so peacefully the day before. Mrs. Lynne stripped me down to my undies. I felt embarrassed being handled naked by someone other than my mother. She placed me on the toilet lid, covered me with a towel, and ran water in the tub.

“Guess the dry spell is over,” she said. “Funny what we call a dry spell out here. Can you imagine it’s ninety-six degrees in New York today? And that doesn’t even include the humidity. If you add in the humidity, they say it’s one-o-six. My sister lives in New York. That’s the East Coast, dear. Do you know where that is?”

“No.”

“Oh, far from here, where the Yankees are. My sister, Thelma, says she left to get away from the rain. But I know better. She always thought she was too good for this town. You don’t think you’re too good for a small town, do you, dear?”

“No.”

“Good. Me neither. Could do without the rain though.”

“Where’s Mommy?” I asked.

She helped me into the tub.

“Your ma got home just before you woke. They carried her up on a board. Shame on your daddy. Not a proper cent to keep her in recovery.”

She wiped me over lightly with the round sponge. I felt like an exposed window display. I hoped she would leave.

“Where’s Betsy?”

“You mean the fortune teller? The absolute last thing your ma needs right now is witchcraft, dear.”

“Fifteen minutes,” Mr. Lynne called. It sounded like he was banging all the lids and pans together in our kitchen.

“Okay,” Mrs. Lynne called back. “That means an hour,” she said to me with a wink.

There was a time when Mr. and Mrs. Lynne were friendly with my parents. But that time ended as my family grew increasingly indiscreet, allowing the neighbors to see and hear too much. The Lynnes would throw great parties at their house with strings of orange lights. Sometimes they’d hire a band. We had become the uninvited. My family was some sort of disease the neighbors didn’t care to be exposed to. And yet, here they were, in our home. Mrs. Lynne and her husband had twinned in that way old couples sometimes do. They both had soft-looking skin, like shaved boiled potatoes. Both with thick threads of gray-black hair and light, creasy eyes. She sat and knitted in the chair, which was still beside the tub from the night before. She let me soak for a good while.

“Is William here?” I asked.

“Who’s William, little one?”

“My brother.”

“Okay. Up you go. I’ll take you to see your ma.”

Mrs. Lynne wrapped me in my towel, carried me through the hall with some effort, and dropped me lightly on my mother’s mattress. She adjusted a cloudy rubber tube that was connected to a glass cylinder and pinned to my mom’s arm. I shuddered at the sight of the needle and tried to stay calm. My mother appeared to be asleep.

“I’ll be here for a few days while your ma heals. She won’t be able to get out of bed or walk for some time. Mr. Lynne is staying too.” She patted my head and left us alone.

My mother squinted. She looked gray and there were large bluish-brown circles around her eyes. Her nose was pink and dark purple, crusted with blood at the nostrils. Seeing her face bruised up was not completely unfamiliar, but the tube dispensing clear liquid drops was alarming, made her look like Frankenstein’s sister.

“Mom?”

She didn’t answer.

“Mom? Why are they staying here?”

“To take care of us.” Her voice was raspy.

“Is William okay?”

“William’s gone. They took everything out of me. Everything.”

I imagined her lungs, intestines, and stomach, rolled into a drawer on a metal platter. Her eyes slowly followed something on the ceiling.

“I can’t have any more children. God is punishing me…for being a bad mother.”

White ink spread under her skin. I wanted to comfort her but thought perhaps it’d be best if I went in search of William instead. I hadn’t seen him yet. I had a nagging feeling he was someplace far off. I hoped he’d be somewhere hiding close by. She just needed to see him and

everything would be right again. As I moved away she took hold of my elbow and pulled me back so I rested beside her.

“I was supposed to have five. Three girls. Two boys. This isn’t the life I was meant to have.”

The idea that my mother could possibly be in the wrong life scared me. The idea that she could evaporate, suddenly, seemed as real as anything else. I’d find her fading limb by limb till she was erased. Who, then, would be my mother? The tears rolled over the bridge of my nose and formed a tiny pool on the pillowcase. I touched it with my finger till it bled into the fabric.

“Oh, honey. Now I’ve gone and upset you more. I’m a terrible mother.”

“No, you’re not.” I turned away. “When is he coming home?”

“Who? Your father?”

“No. William.”

My mother covered her mouth and gripped wildly at her stomach. Her body shook furiously. Her mouth was elastic, choked with anguish. I moved closer to her, pulling my towel tight around my shoulders. She let out a long impaling wail. Mrs. Lynne would have to force her to eat, negotiating bites, eventually finding herself unsympathetic, impatient with my mother’s situation once again. My mother would weep on and off for weeks—saddled with culpability—shrouded in remorse.

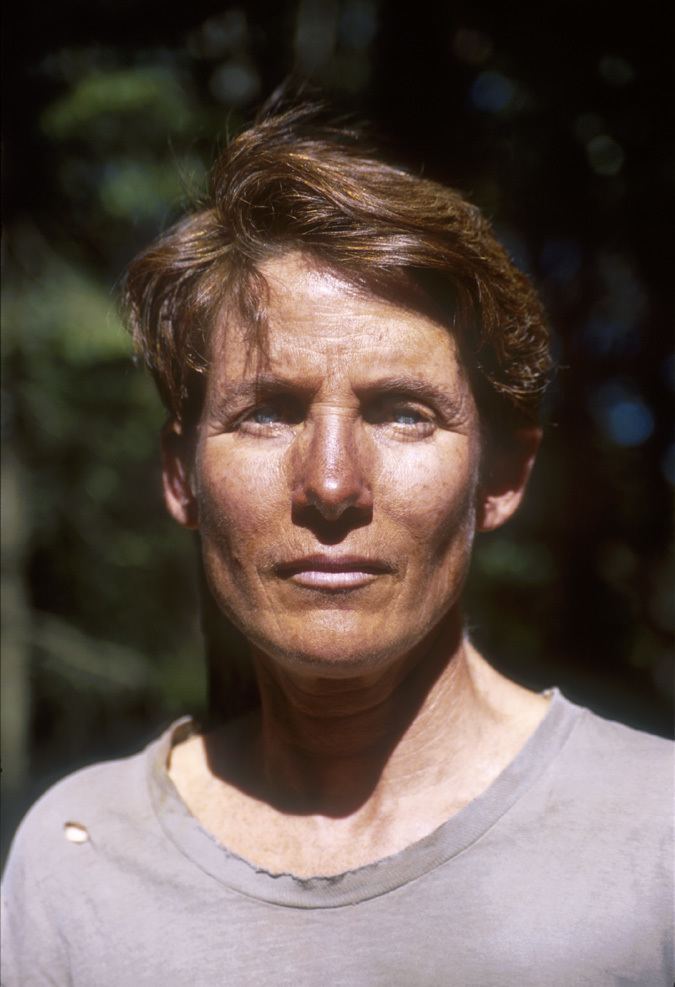

جوليا ديانا — JD Robertson, is an award-winning author, and journalist—A first generation Arab-American, who grew up between worlds, and currently resides somewhere in the middle with a bird’s eye view.