Just a few hours ago, The Washington Post issued an apology for naming Jennie Hodgers, aka Albert Cashier, “one of the more than 400 women who concealed their gender and fought as men during the American Civil War.” They’ve released the following statement: “We’ve deleted this tweet and corrected the podcast episode about Civil War veteran Albert Cashier to remove it from the series about women who won wars and make some corrections to pronoun usage…”

Last year, in a piece at The Guardian, Adam Gabbatt wrote about “a young man called Albert Cashier” who made history, bravely fighting with the 95th Illinois infantry. He went on to say, “Albert Cashier was assigned female at birth.” Gabbatt noted that “Albert Cashier the Musical,” would be running in Chicago through September.

There’s a pivotal mistake made, in this rewrite of history — instead of celebrating the accomplishments and courage of a woman forced to fight sexist limitations under patriarchy, a current narrative is being bolstered, taking away one of the few pages women have in history books.

Albert Cashier was not a man, she was a brave woman, fighting to escape restrictive gender roles.

Albert Cashier was not a man, she was a brave woman, fighting to escape restrictive gender roles.

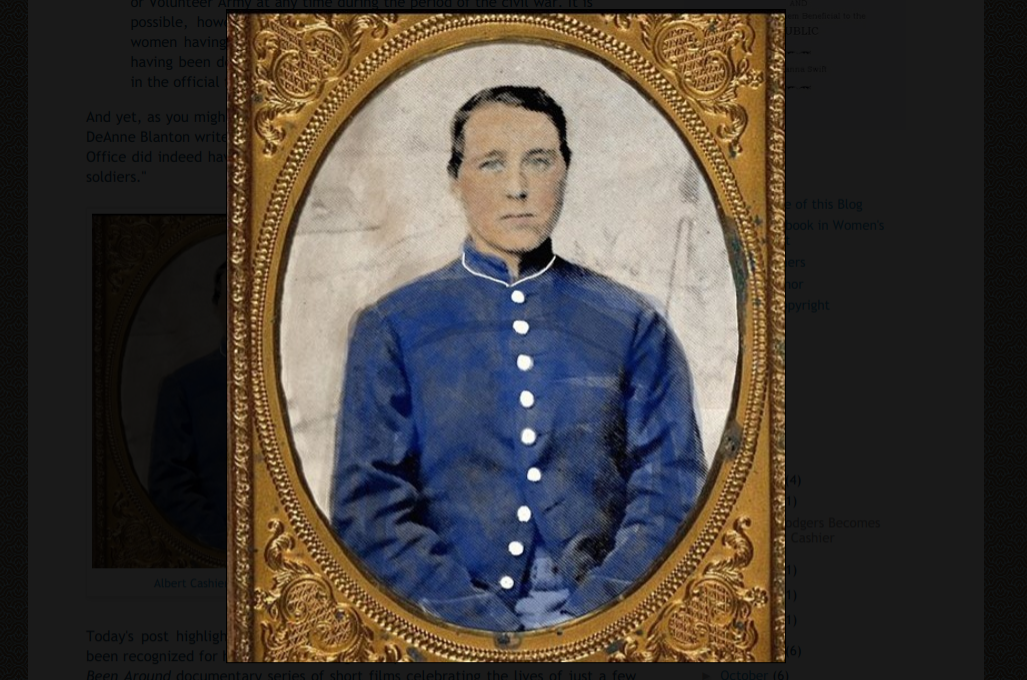

Born in 1844, Jennie Hodgers wanted to serve her country. Like many women in those times, she was suffocated by the limitations of patriarchy, which sent the message that the only thing a woman was fit to serve was dinner. So she tossed her sewing needles aside and bid farewell to the restrictive roles offered to women, like becoming a wife and mother. Rather than face a life of poverty, Jennie Hodgers chose a path of independence and adventure, ultimately becoming the bravest soldier in her company.

“ ‘Albert Cashier’ mustered out of the service with the rest of her regiment on Aug. 17, 1865, and went back to Illinois…Hodgers could not read or write, and the jobs available for an illiterate woman would have sunk her into poverty, or even prostitution. But as a man, she could get by as she had in the Army, working steadily and honestly, and she made an adequate…living as a handyman, a farm laborer and a janitor, turning her work-worn hands to whatever came her way, supplementing her income with a veteran’s pension.”—The New York Times

When her company’s flag was taken down by enemy fire, she brazenly climbed a tree while bullets of enemy snipers surrounded her, and attached the tattered flag to a branch up high.

In 1862, Jennie Hodgers enlisted as an infantryman in the 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment as “Albert Cashier.” She was captured at Vicksburg while on a mission, and escaped by attacking a guard, seizing his gun, and outrunning her captors. When her company’s flag was taken down by enemy fire, she brazenly climbed a tree, while bullets of enemy snipers surrounded her, and attached the tattered flag to a branch up high.

“At the time, women weren’t perceived as equals by any stretch of the imagination. It was the Victorian era and women were mostly confined to the domestic sphere. Both the Union and Confederate armies actually forbade the enlistment of women.” —Smithsonian Magazine

Back in 1862, the physical examination, required of recruits to join the army, only looked at the face, hands, and feet. After Hodgers enlisted, she was able to live a life outside the bounds of a sexist society. Hodgers hid who she was, in order to become the woman she wanted and needed to be.

In order to avoid being discovered, Albert Cashier found ways to bathe and dress alone. She avoided sharing a tent with any of the men. She kept her shirt buttoned to the chin, to hide the place where an Adam’s apple was missing.

Unable to read or write, she’d ‘passed’ as Albert Cashier in order to survive and work in fields she would not have been permitted to otherwise, as a woman.

It wasn’t until decades later, in 1914, when “Albert Cashier” arrived at a psychiatric hospital in Illinois, with symptoms of advanced dementia, that Hodgers’ secret was revealed: Unable to read or write, she’d ‘passed’ as Albert Cashier in order to survive and work in fields she would not have been permitted to otherwise, as a woman. Hodgers, having been discovered to be female, was forced to wear a long skirt for the first time in over 50 years.

In The New York Times, history and women’s studies professor, Jean R. Freedman, explained the impact of such restrictive clothing.

“Unused to walking in the long, cumbersome garments deemed appropriate for her sex, she tripped and fell, breaking a hip that never properly healed. Bedridden and depressed, her health continued to decline, and she died on Oct. 11, 1915.” —The New York Times

If women wanted a life beyond confinement to the house, with no autonomy — financial or otherwise — they had to get creative. Women bound their breasts, wore loose, layered clothing, cut their hair short and rubbed dirt on their faces, in order to look more like young male soldiers.

Women like Jennie chose a life of empowerment, honor, and adventure… Historians have uncovered accounts of hundreds of women who ‘passed’ as men to fight in wars.

Women like Jennie Hodgers chose a life of empowerment, honor, and adventure… Historians have uncovered accounts of hundreds of women who ‘passed’ as men to fight in wars.

“The female Civil War soldiers were not the first American women to fight on the battlefield; Deborah Sampson of Massachusetts served for nearly two years during the Revolution before her sex was discovered in a military hospital. (After being honorably discharged, Sampson received a veteran’s pension for her Revolutionary service, which went to her children upon her death.)” —The New York Times

Oftentimes, women who lived ‘as men,’ just wanted the freedom to do the things only males were legally allowed to do.

Some women, like Francis Clayton, who enlisted as “‘Jack Williams”’ to fight alongside her husband, wanted to go to war to be with family members. There were also women who began ‘passing’ prior to enlisting, as a practical way to avoid poverty (or, in the case of lesbians, psychiatric imprisonment and torture). Oftentimes, women who lived ‘as men,’ just wanted the freedom to do the things only males were legally allowed to do.

“Some women dressed like men and marched off to war with a relative. Others enlisted because they had no means to support themselves after their loved one left home. More than a few were enticed by the wages promised by the army, because money meant freedom from their old roles and the ability to start a new, more independent life. And some female soldiers of the Civil War were simply patriotic and wanted to serve their country.” —Civil War Women

No one questioned a single man’s right to make a living. A woman doing the same thing, would’ve been labeled a spinster, and likely subjected to a terrible fate — ostracized, abused, exploited and living in poverty.

In the town where Hodgers finally settled as Albert Cashier, people wondered why “Albert” never married, but no one thought it was strange for a man to live alone. No one questioned a single man’s right to make a living. A woman doing the same thing, would’ve been labeled a spinster, and likely subjected to a terrible fate — ostracized, abused, exploited and living in poverty.

Women who rejected heterosexuality and marriage, were often subjected to barbaric “remedies,” such as “the application of cocaine solutions, saline cathartics, the surgical ‘liberation’ of adherent clitorises, or even the administration of strychnine by hypodermic.”

Equating a woman’s decision to survive, to not being a woman at all, is about as sexist as it gets. As is equating womanhood to a particular set of clothes, haircuts, names and interests.

Equating a woman’s decision to survive, to not being a woman at all, is about as sexist as it gets. As is equating womanhood to a particular set of clothes, haircuts, names, and interests. These women were not male… They were brave, pioneering women,who were willing to do whatever they had to, in order to experience and accomplish things only men were allowed to do, at the time — Women who have been largely erased from history.

“Their exact number [of female Civil war soldiers] is unknown, because their service had to be clandestine, but the ones whose stories we know offer a fascinating glimpse of women who pushed against the boundaries of their Victorian confinement at a time when American women could not vote, serve on juries, attend most colleges or practice most professions, and who, when they married, lost all property rights in most states.”—The New York Times

After her service was complete, Hodgers kept the identity of Albert Cashier. Living as Albert Cashier, meant she was able to make a living and supplement her income with her veteran’s pension… As Albert Cashier, she voted in elections, long before women were allowed to vote.

After her service was complete, Hodgers kept the identity of Albert Cashier. Living as Albert Cashier, meant she was able to make a living and supplement her income with her veteran’s pension. As Albert Cashier, she was able to work in fields she wouldn’t have been permitted to otherwise, as a woman. As Albert Cashier, she was able to participate in veteran’s gatherings, wear her uniform, and relish in the camaraderie, success and the honor she’d earned. As Albert Cashier, she voted in elections, long before women were allowed to vote. Freedman notes that Hodgers “could not read or write, and the jobs available for an illiterate woman would have sunk her into poverty, or even prostitution.”

In 1977, on Memorial Day, the name Jennie Hodgers was added to a second, larger monument at her gravesite, in Saunemin, Illinois, in addition to another that only read “Albert D.J. Cashier.”

Jennie Hodgers, aka Albert Cashier, is a symbol of defiance and bravery — a pioneer of womankind, who dreamed bigger than the world would allow. Rewriting Jennie Hodgers as a “man,” does a great disservice to her legacy, and erases the sexism that led her to make the choices she did.

Jennie Hodgers, aka Albert Cashier, is a symbol of defiance and bravery — a pioneer of womankind, who dreamed bigger than the world would allow. Rewriting Jennie Hodgers as a “man,” does a great disservice to her legacy, and erases the sexism that led her to make the choices she did.

Jennie Hodgers was a heroine of the best kind — she defied all limitations.

A different version of this article, by Julia Diana Robertson, is published on Feminist Current and Huffington Post.

Julia Diana Robertson is an author and journalist living in New York . Learn more about her work at: juliadianarobertson.com. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaDRobertson. A different version of this article is published at Huffington Post.